Spring Offensive

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1918 Spring Offensive or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser's Battle), also known as the Ludendorff Offensive, was a series of German attacks along the Western Front during World War I, which marked the deepest advances by either side since 1914. The German authorities had realised that their only remaining chance of victory was to defeat the Allies before the overwhelming human and matériel resources of the United States could be deployed. They also had the advantage of nearly 50 divisions freed by the Russian surrender (Treaty of Brest-Litovsk).

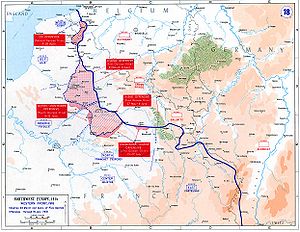

There were four separate German attacks, codenamed Michael, Georgette, Gneisenau, and Blücher-Yorck. They were initially intended to draw forces away from the Channel Ports that were essential for British supply and then attack the ports and other lines of communication. The planning process, however, diluted the strategy.

Contents |

Tactical background

The German Army, with few exceptions, had remained essentially on the defensive in the West in 1915, 1916 and 1917, and its doctrine had focused mostly on defensive tactics. Conversely, the Allied armies had launched most of the offensives on the Western Front. Despite several large scale battles, the frontline changed only very marginally, while causing heavy casualties on both sides. The reason for this was the static trench warfare, in which the available technology at the time gave heavy advantages to the defender. Consequently both sides worked on developing new tactics and techniques to break through fixed enemy defences.

German tactics

On the German side, the German army had concentrated stormtrooper units, with infantry trained in Hutier tactics (after Oskar von Hutier) to infiltrate and bypass enemy front line units, leaving these strongpoints to be "mopped-up" by follow-up troops. The stormtroopers' tactic was to attack and disrupt enemy headquarters, artillery units and supply depots in the rear areas, as well as to occupy territory rapidly. Each major formation "creamed off" its best and fittest soldiers into storm units; several complete divisions were formed from these elite units. This process gave the German army an initial advantage in the attack, but meant that the best formations would suffer disproportionately heavy casualties, while the quality of the remaining formations declined as they were stripped of their best personnel to provide the storm troops.

To enable the initial breakthrough, Lieutenant Colonel Georg Bruchmüller,[4] a German artillery officer, developed the Feuerwalze, an effective and economical artillery bombardment scheme[5]. There were three phases: a brief attack on the enemy's command and communications (headquarters, telephone exchanges etc.), destruction of their artillery and lastly an attack upon the enemy front-line infantry defences. Bombardment would always be brief so as to retain surprise. Bruchmüller's tactics were made possible by the vast numbers of heavy guns (with correspondingly plentiful amounts of ammunition for them) which Germany possessed by 1918. It was possible for the Germans to launch an offensive at almost any vital part of the front without giving the Allies notice of their intentions by moving guns and shells to the threatened sector.

Defensive tactics

In their turn, the Allies had developed defences in depth, reducing the proportion of troops in their front line and pulling reserves and supply dumps back beyond German artillery range. This change had been made after experience of the successful German use of defence in depth during 1917.

In theory, the front line was an "outpost zone" (later renamed the "forward zone"), lightly held by snipers, patrols and machine-gun posts only. Behind was the "battle zone", where the offensive was to be firmly resisted, and behind that again was a "rear zone", where reserves were held ready to counter-attack or seal off penetrations. In theory a British infantry division (with 9 infantry battalions) deployed 3 battalions in the outpost zone, 4 battalions in the battle zone and 2 battalions in the rear zone.[6]

This change had not been completely implemented by the Allies. In particular, in the sector held by the British Fifth Army, which they had recently taken over from French units, the defences were not completed and there were too few troops to hold the complete position in depth. The rear zone existed as outline markings only, and the battle zone consisted of battalion "redoubts" which were not mutually supporting (allowing stormtroopers to penetrate between them).

Michael

On 21 March 1918, the Germans launched a major offensive against the British Fifth Army, and the right wing of the British Third Army.

The artillery bombardment began at 4.40 am on 21 March. The bombardment [hit] targets over an area of 150 square miles, the biggest barrage of the entire war. Over 1,100,000 shells were fired in five hours...[7]

The German armies involved were, from north to south, the Seventeenth Army under Otto von Below, the Second Army under Georg von der Marwitz and the Eighteenth Army under Oskar von Hutier, with a Corps (Gruppe Gayl) from the Seventh Army supporting Hutier's attack. Although the British had learned the approximate time and location of the offensive, the weight of the attack and of the preliminary bombardment was an unpleasant surprise. The Germans were also fortunate in that the morning of the attack was foggy, allowing the stormtroopers leading the attack to penetrate deep into the British positions undetected.

By the end of the first day the British had lost nearly 20,000 dead and 35,000 wounded, and the Germans had broken through at several points on the front of the British Fifth Army. After two days Fifth Army was in full retreat. As they fell back, many of the isolated "redoubts" were left to be surrounded and overwhelmed by the following German infantry. The right wing of Third Army became separated from the retreating Fifth Army, and also retreated to avoid being outflanked.

General Erich Ludendorff, the First Quartermaster-General at Oberste Heeresleitung, the German supreme headquarters, and effectively the commander of the German armies, failed to follow the correct stormtrooper tactics, as described above. His lack of a coherent strategy to accompany the new tactics was expressed in a remark to one of his Army Group commanders, Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, in which he stated, "We chop a hole. The rest follows." Ludendorff's dilemma was that the most important parts of the Allied line were also the most strongly held. Much of the German advance was achieved where it was not strategically significant. Because of this, Ludendorff continually exhausted his forces by attacking strongly entrenched British units. At Arras on 28 March, he launched a hastily-prepared attack (Operation Mars) against the left wing of the British Third Army, to try and widen the breach in the Allied lines, and was repulsed.

The German breakthrough had occurred just to the north of the boundary between the French and British armies. The French commander-in-chief, General Pétain, sent reinforcements to the sector too slowly in the opinion of the British commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Haig, and the British government. The Allies reacted by appointing the French General Ferdinand Foch to coordinate all Allied activity in France, and subsequently as commander-in-chief of all Allied forces everywhere.

After a few days, the German advance began to falter, as the infantry became exhausted and it became increasingly difficult to move artillery and supplies forward to support them. Fresh British and Australian units were moved to the vital rail centre of Amiens and the defence began to stiffen. After fruitless attempts to capture Amiens, Ludendorff called off Operation Michael on 5 April. By the standards of the time, there had been a substantial advance. It was, however, of little value; a Pyrrhic victory in terms of the casualties suffered by the crack troops, as the vital positions of Amiens and Arras remained in Allied hands. The newly-won territory was difficult to traverse, as much of it consisted of the shell-torn wilderness left by the 1916 Battle of the Somme, and would later be difficult to defend against Allied counterattacks.

The Allies lost nearly 255,000 men (British, British Empire, French and American). They also lost 1,300 artillery pieces and 200 tanks.[8] All of this could be replaced, either from British factories or from American manpower. German troop losses were 239,000 men, many of them specialist shocktroops (Stoßtruppen) who were irreplaceable.[8] In terms of morale, the initial German jubilation at the successful opening of the offensive soon turned to disappointment as it became clear that the attack had not achieved decisive results.

Georgette

Michael had drawn British forces to defend Amiens, leaving the rail route through Hazebrouck and the approaches to the Channel ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk vulnerable. German success here could choke the British into defeat.

The attack started on 9 April after a Feuerwalze. The main attack was made on the sector defended by the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps, which was tired after an entire year spent in the trenches, and just when they were scheduled to be replaced in the line by fresh British troops. Despite a desperate defense in which they lost more than 7,000 men, the Portuguese defenders and the British on their northern flank were rapidly overrun. However, the British defenders on the southern flank held firm on the line of the La Bassée Canal. The next day, the Germans widened their attack to the north, forcing the defenders of Armentieres to withdraw before they were surrounded, and capturing most of the Messines Ridge. By the end of the day, the few British divisions in reserve were hard-pressed to hold a line along the River Lys.

Without French reinforcements, it was feared that the Germans could advance the remaining 15 miles (24 km) to the ports within a week. The commander of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, issued an "Order of the Day" on 11 April stating, "With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause, each one of us must fight on to the end."

However, the German offensive had stalled because of logistical problems and exposed flanks. Counterattacks by British, French, American, and ANZAC forces slowed and stopped the German advance. Ludendorff ended Georgette on 29 April.

As with Michael, losses were roughly equal, approximately 110,000 men wounded or killed, each.[9] Again, the strategic results were disappointing for the Germans. Hazebrouck remained in Allied hands and the flanks of the German salient were vulnerable. The British abandoned the comparatively worthless territory they had captured at vast cost the previous year around Ypres, freeing several divisions to face the German attackers.

Blücher-Yorck

While Georgette ground to a halt, a new attack on French positions was planned to draw forces further away from the Channel and allow renewed German progress in the north. The strategic objective remained to split the British and the French and gain victory before American forces could make their presence felt on the battlefield.

The German attack took place on 27 May, between Soissons and Rheims. The sector was partly held by six depleted British divisions which were "resting" after their exertions earlier in the year. In this sector, the defences had not been developed in depth, mainly due to the obstinacy of the commander of the French Sixth Army, General Denis Auguste Duchêne. As a result, the Feuerwalze was very effective and the Allied front, with a few notable exceptions, collapsed. Duchêne's massing of his troops in the forward trenches also meant there were no local reserves to delay the Germans once the front had broken. Despite French and British resistance on the flanks, German troops advanced to the Marne River and Paris seemed a realistic objective. However, United States Army machine-gunners and Senegalese sharpshooters halted the German advance at Château-Thierry, with United States Marines also heavily engaged at Belleau Wood.

Yet again, losses were much the same on each side: 137,000 Allied and 130,000 German casualties up to 6 June[10]. German losses were again mainly from the difficult-to-replace assault divisions.

Gneisenau

Ludendorff sought to extend Blücher-Yorck westwards with Operation Gneisenau, intending to draw yet more Allied reserves south and to link with the German salient at Amiens.

The French had been warned of this attack (the Battle of Matz (French: Bataille du Matz)) by information from German prisoners and their defence in depth reduced the impact of the artillery bombardment on 9 June. Nonetheless, the German advance (comprising of 21 divisions attacking over a 23 mile front) along the Matz River was impressive (resulting in an advance of nine miles (14 km)), despite fierce French and American resistance. At Compiègne, a sudden French counter-attack by four divisions and 150 tanks (under General Charles Mangin) on 11 June caught the Germans by surprise and halted their advance. Gneisenau was called off the following day.

Losses were approximately 35,000 Allied and 30,000 German.

Last German attack

The final offensive launched by Ludendorff on 15 July was a renewed attempt to draw Allied reserves south from Flanders, and to expand the salient created by Blücher-Yorck eastwards. An attack east of Rheims was thwarted by the French defence in depth. Although German troops southwest of Rheims succeeded in crossing the River Marne, the French launched a major offensive of their own on the west side of the salient on 18 July, threatening to cut off the Germans in the salient. Although Ludendorff was able to hold off this attack and successfully evacuate the salient, the initiative had clearly passed to the Allies, who were shortly to begin the Hundred Days Offensive which effectively ended the war.

Strategic Impact

The Kaiserschlacht series of offensives had yielded large territorial gains for the Germans, in First World War terms. However, the strategic objective of a quick victory was not achieved and the German armies were severely depleted, exhausted and in exposed positions. The territorial gains were in the form of salients which greatly increased the length of the line that would have to be defended when allied reinforcements gave the allies the initiative. In six months the strength of the German army had fallen from 5.1 million fighting men to 4.2 million. Manpower was exhausted. The German High Command predicted they would need 200,000 men per month to make good the losses suffered, but even by drawing on the next annual class of eighteen year olds, only 300,000 recruits would be available for the year. Even worse, they lost most of their best trained men: stormtrooper tactics had them leading the attacks. Even so, about a million German soldiers remained tied up in the east until the end of the war, attempting to run a short-lived addition to the German Empire in Europe. German political ambitions remained extravagant until the very end.

The Allies had been badly hurt but not broken. The lack of a unified high command was partly rectified by the appointment of Marshal Foch to the supreme command, and coordination would improve in later Allied operations. American troops were for the first time used as independent formations and had proven themselves. Their presence counterbalanced the serious manpower shortages that Britain and France were experiencing after four years of war.

References

- ↑ Churchill, "The World Crisis, Vol. 2". German casualties from "Reichsarchiv 1918"

- ↑ Churchill, "The World Crisis, Vol. 2". British casualties from "Military Effort of the British Empire"

- ↑ Churchill, "The World Crisis, Vol. 2". French casualties from "Official Returns to the Chamber, March 29, 1922"

- ↑ Bruchmüller biography.

- ↑ D T Zabecki, The German 1918 Offensives: A Case Study of The Operational Level of War, Taylor & Francis, 2005, p 56

- ↑ Blaxland, p.28

- ↑ historyofwar.org

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Marix Evans, p.63

- ↑ Marix Evans, p.81

- ↑ Marix Evans, p.105

Sources

- Blaxland, Gregory [1968] (1981) Amiens 1918, War in the twentieth century series, London: W. H. Allen, ISBN 0-352-30833-8

- Chodorow, Stanley [1969] (1989) Mainstream of Civilization, 5th ed., San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 0-15-551579-9

- Gray, Randal (1991) Kaiserschlacht, 1918: The Final German Offensive, Osprey Campaign Series 11, London: Osprey, ISBN 1-85532-157-2

- Griffith, Paddy (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: British Army's Art of Attack. 1916–18. Yale. ISBN 0300066635.

- Keegan, John (1999) The First World War, London: Pimlico, ISBN 9780712666459

- Marix Evans, Martin (2002) 1918: The Year of Victories, Arcturus Military History Series, London: Arcturus, ISBN 0-572-02838-5

- Zabecki, David T. (2006) The German 1918 Offensives. A Case Study in the Operational Level of War, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-35600-8

Further reading

- Pitt, Barrie [1962] (2003) 1918 The Last Act, Pen & Sword Military Classics series, Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books Ltd, ISBN 0-85052-974-3

See also

- Journey's End, a play set during the early stages of the offensive

- Spring Offensive, a poem by Wilfred Owen

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||